- Players

- Teams

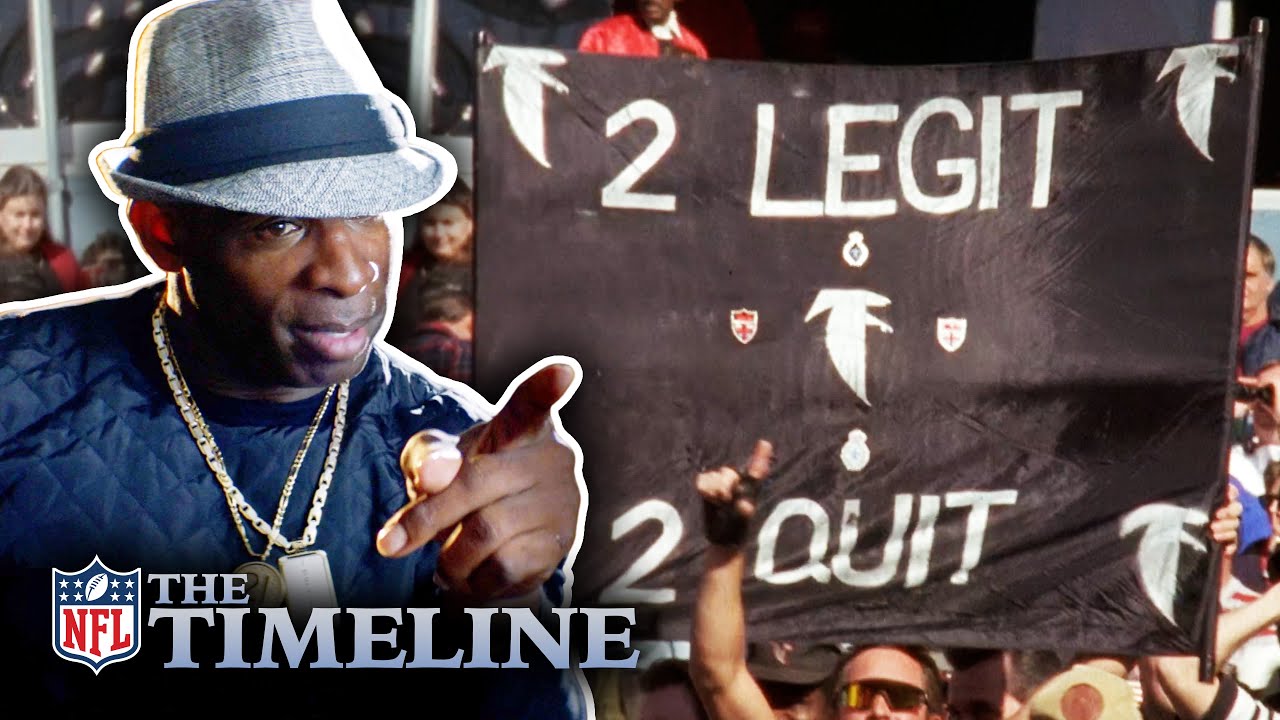

- Atlanta

- Arizona

- Baltimore

- Boston

- Buffalo

- Calgary

- Carolina

- Chicago

- Cincinnati

- Cleveland

- Columbus

- Dallas

- Denver

- Detroit

- Edmonton

- Houston

- Indiana

- Jacksonville

- Kansas City

- Las Vegas

- Los Angeles

- Louisville

- Miami

- Milwaukee

- Minnesota

- Montreal

- New Orleans

- New York

- Oakland

- Oklahoma

- Orlando

- Ottawa

- Philadelphia

- Phoenix

- Pittsburgh

- Portland

- San Antonio

- San Diego

- Seattle

- San Francisco

- St. Louis

- Tampa Bay

- Tennessee

- Toronto

- Utah

- Vancouver

- Washington DC

- Winnipeg

- Leagues

- Stadiums

- More

All-America Football Conference (AAFC)

1948 AAFC Audio & Video Clips

Recap

Although 1947 had been a successful season for the AAFC in many respects, the league still lost money. In 1948, attendance in both leagues declined, and negotiations to end the war became serious.

One factor affecting AAFC attendance was the gap between the league's best and worst teams. To counter this, Commissioner Ingram attempted to get the strongest teams to distribute some players to the weakest. He was modestly successful: the Browns sent rookie quarterback Y. A. Tittle to the Colts, who enjoyed their first good season, and the Yankees were generous enough to fall into mediocrity. However, 1948 featured extremes despite Ingram's efforts.

For the first time, the division races were close. One featured excellence, the other mediocrity.

The 1948 AAFC Draft was held on December 16, 1947 in New York City, NY. Tony Minisi was the first overall selection. In the West, San Francisco and Cleveland both remained undefeated far into the season. On November 14, nearly 83,000 (a record) in Cleveland Municipal Stadium watched the 9–0 Browns win a 14–7 defensive struggle over the 10–0 49ers. They met again two weeks later in San Francisco, with the Browns now 12–0 and the 49ers 11–1. The Browns again won narrowly, this time 31–28, clinching first place.

The rematch concluded an AAFC Thanksgiving week promotion: the Browns played three games in eight days. New Dodgers' part-owner Branch Rickey (of baseball fame) suggested this experiment, and the Browns were chosen as the guinea pigs. They survived unscathed, and went on to complete an unprecedented 14–0 regular season.

The 49ers finished a heartbreaking second (and out of the postseason) at 12–2. Los Angeles followed at 7–7, and Chicago again finished last at 1–13. The quarterbacks of the two outstanding teams, Cleveland's Otto Graham and San Francisco's Frankie Albert, shared the MVP.

In the East, Buffalo and Baltimore tied at a mediocre 7–7, just ahead of 6–8 New York. Brooklyn was last at 2–12. Buffalo won a playoff and the dubious privilege of meeting Cleveland for the title.

Cleveland won the title in a predictable rout, 49–7. With pro football's second perfect season (after the 1937 Los Angeles Bulldogs of the second American Football League) and an 18-game winning streak and a 29-game unbeaten streak in progress, the Browns were making history. Since then, only the 1972 Miami Dolphins team managed to win its league championship with an unblemished record. The Pro Football Hall of Fame recognizes the Browns' latter streak as the longest in the history of professional football.

The NFL also had a problem with imbalance. Nearly every title game from 1933 to 1946 featured either the Giants or Redskins from the East against either the Bears or Packers from the West.

But in the late 1940s new powers rose in the NFL, as the Cardinals, Eagles, and Rams all won titles, and the Steelers reached a playoff. All these teams had long histories of futility and had merged or suspended operations during the war. (In fact, the Cardinals were winless from mid-1942 to mid-1945, including a 0–10 merged season with the Steelers.)

Adding to the drama, the division races were often tight. Decades before Pete Rozelle, Bert Bell promoted parity by purposely matching strong teams early in the season, keeping them from getting far ahead in the standings. All this contrasted sharply with the AAFC.

The war was getting increasingly costly thanks to rising salaries and dropping attendance. Nearly every team in both leagues lost money – enough that in December, the NFL officially acknowledged the AAFC as peace talks almost succeeded in ending the war. However, the AAFC wanted four of its teams to be admitted into the NFL, while the NFL was willing to admit only the Browns and 49ers. Although the survival of its Brooklyn and Chicago teams was now in doubt, the AAFC decided to continue the fight.

I sincerely appreciate the research work, and the information being shared. It is important and interesting history.